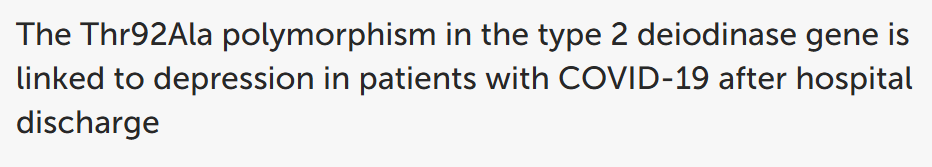

Thyroid hormones, particularly triiodothyronine (T3), are central to metabolic regulation, energy expenditure, and adaptation to environmental stressors like starvation and cold. The conversion of thyroxine (T4) to the more active T3 is mediated primarily by deiodinase enzymes, with type 2 deiodinase (DIO2) playing a key role in peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle, brain, and brown adipose tissue. Genetic variations in DIO2, especially the Thr92Ala polymorphism (rs225014), can impair this conversion, leading to reduced intracellular T3 availability despite normal serum levels.

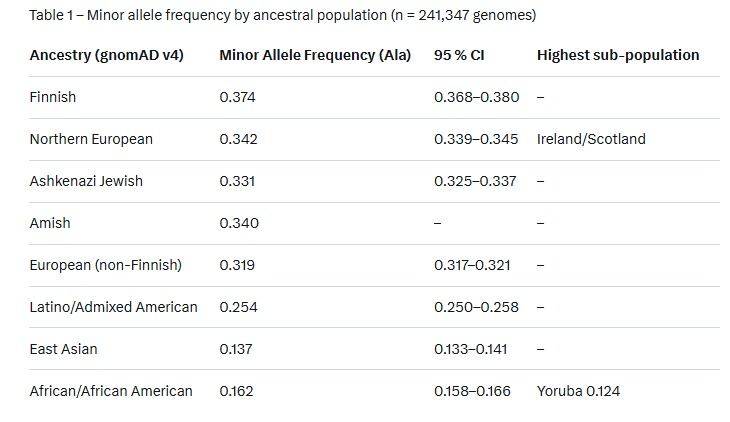

This inefficiency is not uniform across populations; evolutionary pressures from historical famines and cold climates have shaped allele frequencies, making northern Europeans (e.g., those of Scandinavian or Celtic descent) more susceptible to persistent metabolic slowdowns after stress, while populations of African descent exhibit greater resilience.

A patient’s family history may reveal that many people in his family have been diagnosed with “thyroid problems”. Thyroid system problems, in general, tend to run in families. There seems to be a hereditary component. It seems that those who are most prone to developing this complex thyroid problem are those whose ancestors survived famine, such as Irish, Scot, Welsh, American Indian, Russian, etc. Most susceptible of all seem to be those who are part Irish, and part American Indian. There also may be an independent correlation with the genetic makeup that is consistent with people having light colored skin, freckles, red highlights or red hair, and light-colored eyes. But under severe circumstances people of any nationality can develop this problem. It seems that about 80% of sufferers are women (childbirth is more stressful than fasting, and women nervous systems perceive fasting as more stressful than men due to evolution and the necessity to keep a higher fat % for optimal functioning.).

Historical famines, such as those in Ireland (Great Famine, 1845–1852) and Scotland (Highland Potato Famine, 1846–1857), exerted strong selective pressure on thyroid-related genes. Ancestors who survived these events likely carried variants favoring energy conservation—downregulating T3 production to slow basal metabolic rate (BMR) and preserve fat stores. This adaptation, while life-saving during caloric scarcity, can become maladaptive in modern environments with abundant food but chronic low-level stressors (e.g., psychological stress, infections). In contrast, African populations, originating from equatorial regions with more stable food availability and less extreme cold, evolved under different pressures, resulting in lower frequencies of these variants and better T3 rebound post-stress.

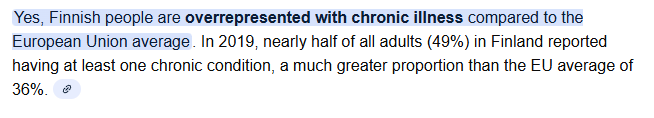

Naturally, you'd want to ask a question like: "Do Finnish people have more chronic illnesses compared to other nationalities?" and then Google says:

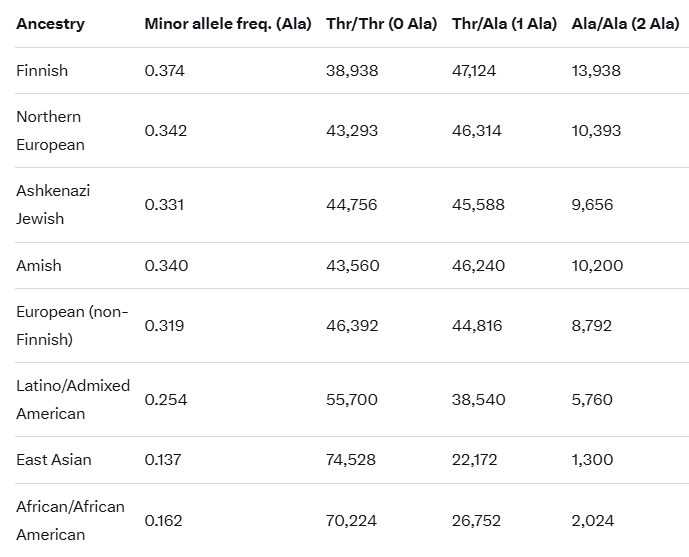

Ok, but let's compare this again, to make a point. Imagine each Ancestry category has 100,000 people in it. If we were to separate them by possible genotypes for the DIO2 Thr92Ala variant, we'd get something like this.

Keep in mind that the Thr/Thr genotype has almost no problems with energy during fasting and stress. In contrast, the Ala/Ala genotype has incredible problems with sustained mental stress, caloric restriction, and severe infections. A Finnish person is 10x more likely to have this problem than someone of East Asian descent. But it also means that the Thr/Ala heterozygous genotype shares some of the issues, even if they should not be as severe and are much easier to reverse with something like the Scorch Protocol. If you're able to do a DNA test, do it. And if you find out that you are the Thr/Thr genotype, then you'll know that the T3 part of the Scorch Protocol may not work for you (I would still run it, though).